Odyssey-Influenced Novels: Family and Ghosts (Part 2 of an ongoing series)

Nerissa Nields

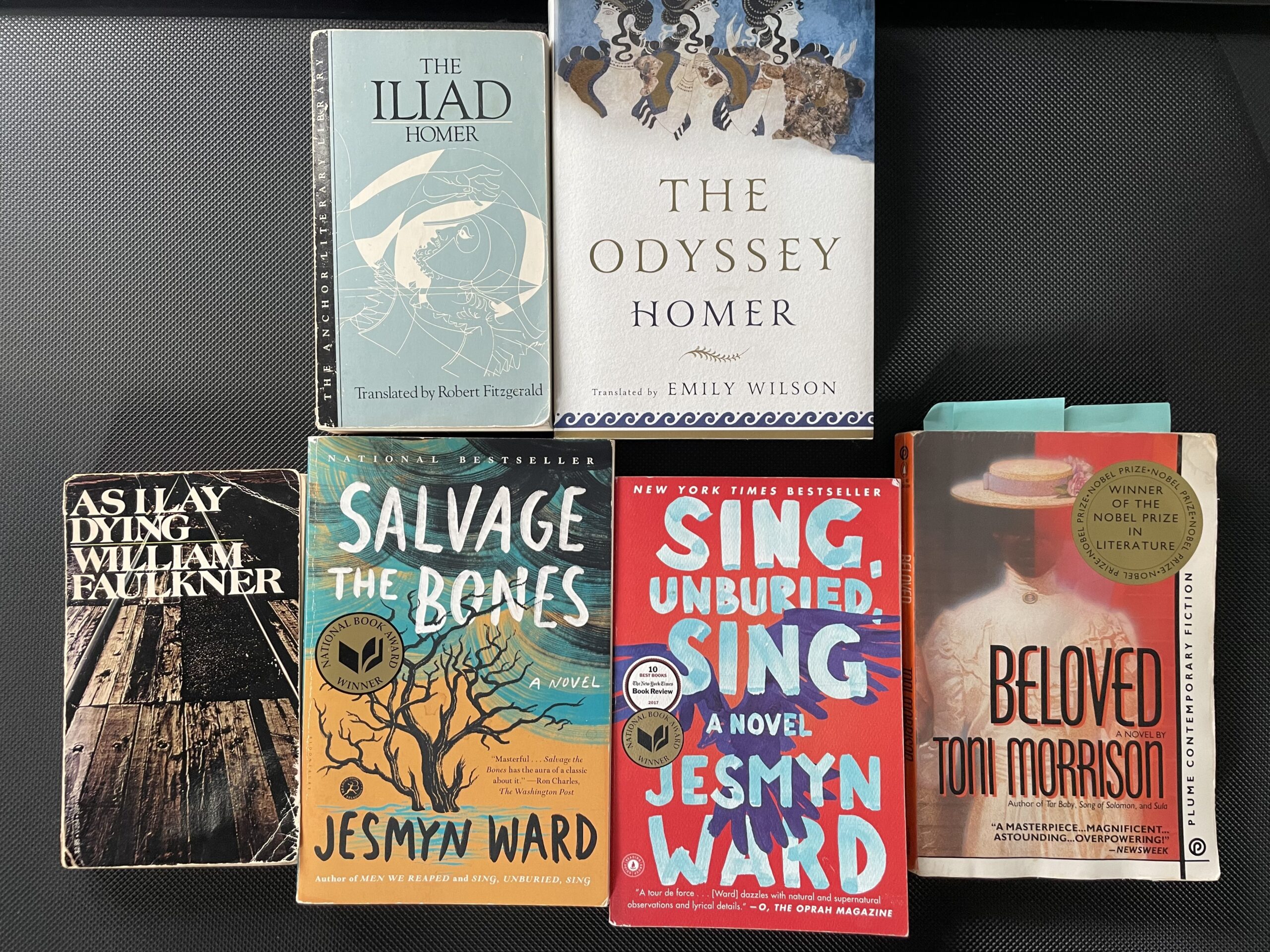

As I Lay Dying and Sing, Unburied, Sing.

As predicted, I now have my manuscript back for the novel Pimmit Run, the first in the series of books about The Big Idea, a family folk-rock band from a small city in Western MA. So this will likely be the last essay before I come up for air again in early November. This is the second in a series of essays about what I’ll call “road novels,” the stories that share The Odyssey as common ancestor. To read the first essay, go here.

William Faulkner has Yoknapatawpha County; Jesmyn Ward has Bois Sauvage –-both in Mississippi––and their fictional places gave me permission to create the town of Pimmit, Massachusetts. Both Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing share important elements––namely family and road––with my yet-untitled second novel in the trilogy about The Big Idea, my family folk-rock band.

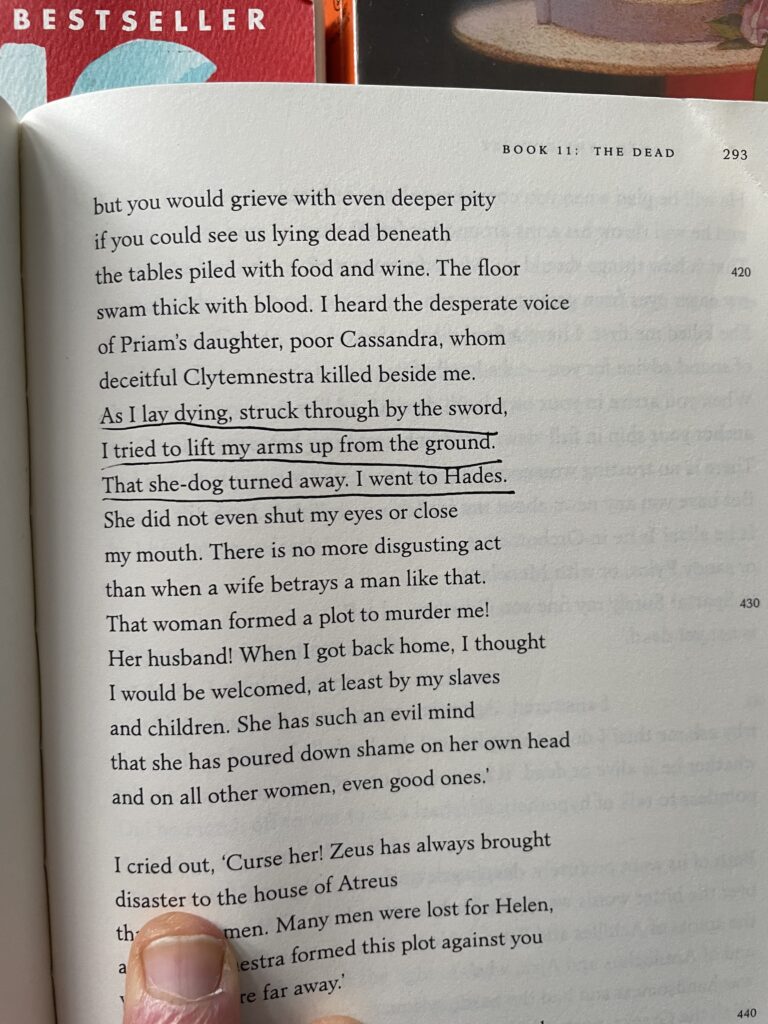

Faulkner’s title for As I Lay Dying comes from a line uttered by Agamemnon, the dead leader of the Greeks, during Odysseus’s visit to Hades’ Underworld.

As I lay dying, struck through by the sword

I tried to lift my arms up from the ground.

That she-dog turned away. I went to Hades.

(The Odyssey, Book 11, lines 424-426)[i]

With this, the author signals his inspiration comes not from the joyful and heroic return home, but from the more complicated, darker aspects of The Odyssey, specifically the parallel story of Agamemnon’s betrayal and murder at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. Indeed, Faulkner’s is a kind of anti-Odyssey. Anse is an anti-Laertes; Addie an Anti-Penelope; all the sons anti-Telemachuses.[ii] It’s as if we’ve stepped into a nightmare version of The Odyssey, as if we were stepping into Agamemnon’s story––where the wife is a betraying murderer––and not Odysseus’s, where the wife, Penelope, is a loyal co-conspirator.

If honor and hospitality are the guiding tropes of The Odyssey, deceit and betrayal rule the Bundren family. The universally despised and dishonest Anse—the family’s patriarch––betrays Addie by marrying her kinswoman the same day he buries his wife. Addie herself has betrayed her marriage by having an affair with the local minister, which produces her son, Jewel. Jewel is betrayed by Anse, who sells Jewel’s beloved horse after his mules drown in the Styx-like river on the road from their shabby farm in Yoknapatawpha to the city of Jefferson. Anse betrays his daughter Dewey Dell by insisting she give him the ten dollars she needs to end her pregnancy in order to help him buy the false teeth he so badly wants. Anse also acts perversely by refusing the hospitality of his hosts, which serves to deprive his children of decent food and lodging. (Jesmyn Ward’s Leonie also refuses food for her children, continuously turning down hospitality). The Bundren family members thoughtlessly apply concrete to brother Cash’s broken leg, which results in a grave infection and permanent damage. Finally, in the ultimate betrayal and one of the coldest, cruelest scenes in the novel, the family members gang up on poor Darl, the second son and our most insightful narrator, turning him over to wardens from an insane asylum.

In Faulkner’s novel, there is no hero, no Odysseus-like figure. He uses no fewer than fifteen narrators, effectively rendering none of them completely trustworthy. The reader must rely on the composite of points of view in order to discern the emotional truth of what is happening. When we’re in Dewey Dell’s or Vardaman’s head, our experience is occluded by how limited their intellect is, and how preoccupied each is with their own concerns. When we’re in the more objective minds of outsiders like Tull or Cora (the neighbors) or Peabody (the doctor), we see that no one has much respect for patriarch Anse, and all pity their dead mother Addie. When we are in Addie’s head, we hear the language of the Anti-Odyssey: her words are full of hatred of life, hatred of her family members (excepting Jewel) and, through a monologue using stream-of-consciousness, a complete rebuttal of Molly Bloom’s famous “yes” in Joyce’s Ulysses.[iii] We see Addie as unrepentant Clytemnestra.

We see how Cash understands his brother Darl’s madness as a real disability and believes Darl might be better off in an institution, but we also see Darl’s own thoughts and assessment. Darl is by far the most insightful and poetic narrator, and perhaps we are so bewitched by his prose, we lose sight of indications of madness. Significantly, Darl does not narrate the moment we understand him to “hear” Addie’s voice in the coffin (talking with ghosts). Instead, we learn this from the not entirely trustworthy Vardaman:

“Hear?” Darl says. “Put your ear close.”

I put my ear close and I can hear her. Only I can’t tell what she is saying.

“What is she saying, Darl?” I say. “Who is she talking to?”

“She’s talking to God,” Darl says. “She is calling on Him to help her.”

“What does she want Him to do?” I say.

“She wants Him to hide her away out of the sight of man,” Darl says.

“Why does she want to hide her away from the sight of man, Darl?”

“So she can lay down her life,” Darl says…”We must let her be quiet.” (p. 204-205)

Indeed, we have just learned from Addie herself that this is true. Her persistent wish is to get away from her family “so I could be quiet and hate them” (p. 161). Her credo comes from her own father, who said that “the reason for living was to get ready to stay dead for a long time” (p. 161). This belief only intensified after she became a mother and wife. It was “when Darl was born I asked Anse to promise to take me back to Jefferson when I died because I knew father had been right” (p. 165). All very Underworld.

Because Faulkner uses so many points of view, we see how others view Darl’s burning down of the Bundren family’s host’s barn (a repudiation of the Greek codes about hosting and being a good guest in The Odyssey.[iv]) We also see Darl’s reason for burning down the barn. Even if he is insane and hearing things, we know that he alone of his family has correctly assessed Addie’s wishes. We hear from practically every outside-the-family narrator that this notion to honor Addie’s wish to be buried in Jefferson has become grotesque. Surely she didn’t mean for the her body to rot and attract the vultures that plague the Bundrens as they lug Addie’s dead body in a wagon on their forty-mile trek. Because we have access to Addie’s true wishes, we are heart-broken when we see how Darl is treated, and also when we lose Darl as a narrator.

In fact, by the novel’s end, the entire trip has lost its purpose; we see it as an unqualified disaster since each character loses something precious because of their venture. Cash loses his leg, Darl loses his freedom, Dewey Dell loses her chance to abort the fetus she is carrying, Jewel loses the one thing he loves––his horse. Only Anse gets what he wants: false teeth and a new wife to do all the thankless tasks Addie won’t be there to do anymore.

In Sing, Unburied, Sing, Leonie’s journey is never presented as heroic; even she understands it as an escape. In her title, Ward invokes the opening of The Iliad, inviting the muse, as Homer does, to sing, signaling that this novel will have a different quality of homecoming from Odysseus’s. Instead, as with Faulkner’s title, we are plunged directly into the underworld:

…heavenly goddess, sing!

That wrath which hurl’d to Pluto’s gloomy reign

The souls of mighty chiefs untimely slain;

Whose limbs unburied on the naked shore,

Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore… ––The Iliad, lines 2-6, translation Alexander Pope.

The muse in this tale is the voice of the “unburied.” In Ancient Greek tradition, there was nothing worse or more shameful to a family than leaving one’s dead family member without proper burial rites.[v] When Jojo asks his grandmother Mam, the novel’s matriarch, if she will be a ghost when she dies, she says:

“Can’t say for sure. But I don’t think so. I think that only happens when the dying is bad. Violent. The old folks always told me that when someone dies in a bad way, sometimes it’s so awful that even God can’t bear to watch, and then half your spirit stays behind and wanders, wanting peace the way a thirsty man seeks water.” She frowns, two fishhooks dimpling down. “That ain’t my way” (Sing, Unburied, Sing, p. 236).

“Mighty chiefs untimely slain” points to these ghosts: Black men in America who have been murdered in obscene numbers since the years post-slavery. The novel has a lot to say about the particular difficulties of being Black in America, beginning with a close look at two of the central male characters.

Jojo has just turned thirteen, and is trying to figure out how to be a man by studying his grandfather, River. This first scene calls to mind another myth from Antiquity: that of Abraham and Isaac with the sacrifice of the goat—and the imagery returns later in the novel as we meet Richie, an incarcerated 12-year old, a ghost who cannot get to the underworld—an “unburied.” It is revealed that River is the one who actually killed Richie to prevent a much more violent and drawn out murder.[vii] We also learn that Jojo’s uncle Given was murdered by white boys on a hunting expedition turned deadly. When she is high, Jojo’s mother Leonie is able to see Given, even interact with him. Ghosts are essential characters in the novel–Richie narrates three of the chapters. Just as Leonie sees Given, so Jojo, her son, sees Richie.

Like As I Lay Dying, Ward’s novel is rife with dogs and vultures. In Sing, Unburied, Sing, River, the beneficent patriarch of the family has a gift with dogs, but this gift leads to his compromised role in participating in the death of Richie. After this point, he can no longer stomach dogs; all Ward’s imagery of them involves murder and excrement. The vultures appear at various points in Sing, most notably as a kind of ghostly Greek chorus in the last chapter.

“I think of ghosts and haunting as just being alert. If you are really alert, you see the life that exists beyond the life that’s on top.” Toni Morrison writes.[viii] As with Beloved, the reader is forced to confront the questions around the characters’ sanity. Are these characters really seeing ghosts? Are the ghosts in the haunted minds of the characters? InBeloved, Sethe’s mother Baby Suggs, says, “Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with a dead Negro’s grief” (Beloved, p. 6). Ward fully metabolizes this concept to write her novel, just as she uses Faulkner’s rich and poetic language and multiple narrators; just as she uses the essential structure of The Odyssey. All these works are part of her heritage and part of her ongoing conversation with her fellow writers.

In both As I Lay Dying and Sing, Unburied, Sing, external atrocities rain down on the traveling family (Dewey Dell’s pregnancy and the deceitful pharmacist MacGowan tricking her into a rape; the breaking of Cash’s leg; the vultures that circle around their final entrance into Jefferson; Riv’s incarceration, Richie’s incarceration and later, his murder; Mam’s cancer; the death of Given; Leonie’s addiction), but in Faulkner, it is the internal harms that create the most pain: the betrayals by Anse, the betrayal of Darl. In Ward, the forces of racism are more problematic than any individual weaknesses of Jojo’s family members. Because of this, we find Jojo’s family much more sympathetic than the Bundrens.

Additionally, Jojo’s family has elements the Bundrens lack: a living matriarch who has the powers of a Circe. Mam is a healer, and her magic is powerful and undeniable. Her clairvoyance is a gift inherited by both Leonie and Jojo. Unlike Addie, Mam loves her family unequivocally. In fact, Mam is the Penelope in this tale: faithful and clear-eyed. It is she who leads Given to the Underworld, taking him with her when she dies, essentially giving him his proper death rites. She instructs Leonie to concoct the medicinal herbs that will allow her to die. Yes, Mam begs for death in a way that is reminiscent of Addie Bundren’s “The reason for living is to get ready to stay dead.” But both women invoke Penelope’s clear-sightedness here; Addie in a monologue that echoes Joyce’s Molly Bloom’s, who is, of course, a Penelope figure. Both invoke a pinpointing look at the truth that, with the exceptions of Darl and Jojo, most of the other characters aren’t ready to see.

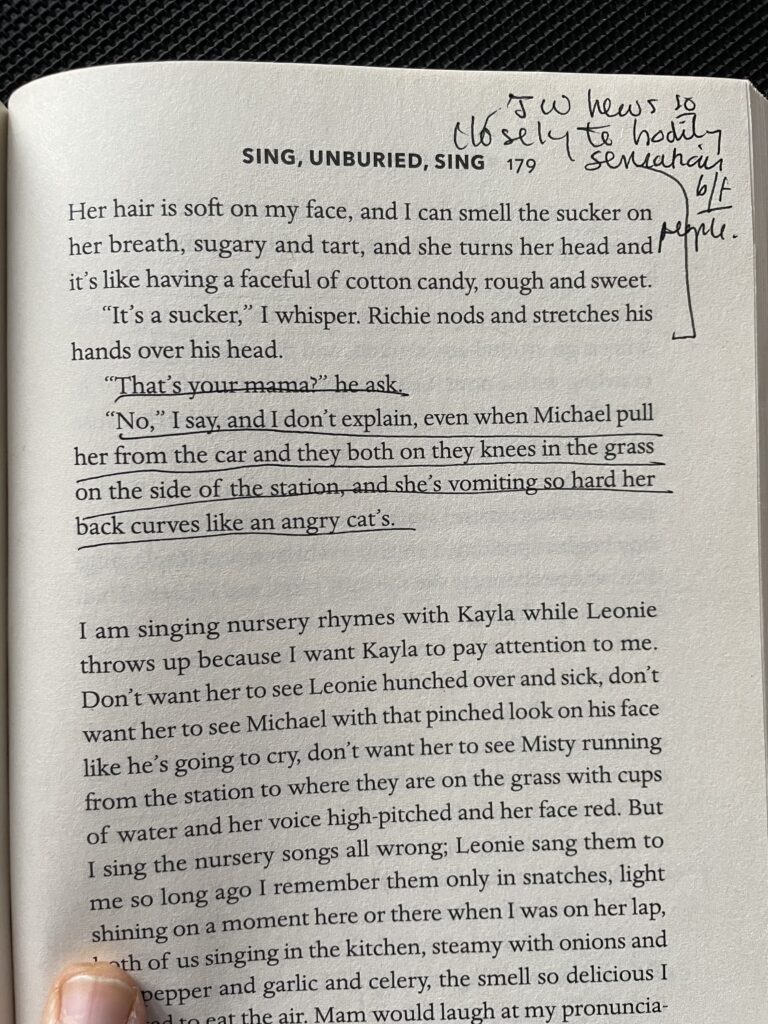

Ward’s dead, like Faulkner’s, are carried in a vehicle across the state of Mississippi. Though Mam “lays dying” until the end of the novel, I would argue that the real death is Leonie’s motherhood, and to some extent Leonie herself. Leonie’s insistence on traveling to pick up Michael from the penitentiary (while participating in a drug deal on the way) is a choice to be buried alive by meth and by a relationship that is inherently self-destructive. What she is really burying is her chance to be a mother to Jojo and Kayla.

If ghosts exist, as Mam says, only “when the dying’s bad” p. 236, then Leonie is doomed to be one of them. Whereas when Jojo goes looking for Mam after her death, we know Mam has made it. Jojo only finds Richie.

I know part of me been waiting on Mam. Been hoping I’d run into her on one of my walks. And when I see him [Richie], I know it ain’t never gonna be Mam….that I’m never gonna see her or hear Uncle Given call me nephew again” p. 280.

Although Sing, Unburied, Sing is unquestionably sad, even tragic, its ending is infinitely more hopeful than that of As I Lay Dying. Jesmyn Ward calls on her literary ghosts—everyone from Homer to the Old Testament to Faulkner to Toni Morrison to George Saunders, but her Kayla, Leonie’s youngest, a three-year-old spark, provides a good metaphor for how a writer can be an amalgam of all her literary ancestors and still present as entirely herself. As Jojo says of his beloved younger sister, “Her eyes Michael’s, her nose Leonie’s, the set of her shoulders Pop’s, and the way she looks upward, like she is measuring the tree, all Mam. But something about the way she stands, the way she takes all the pieces of everybody and holds them together, is all her, Kayla” (p. 284). Fittingly, Kayla also has the last word. In the stunning finale, Jojo tells us that he sees the many ghosts, like vultures, perched in the trees. But it is Kayla who insists on directing them to “Go home.”

The ghosts shudder, but they do not leave. They sway with open mouths again. Kayla raises one arm in the air, palm up, like she’s trying to soothe Casper, but the ghosts don’t still, don’t rise, don’t ascend and disappear. They stay. So Kayla begins to sing, a song of mismatched, half-garbled words, nothing that I can understand. Only the melody, which is low but as loud as the swish and sway of the trees, that cuts their whispering but twines with it at the same time. And the ghosts open their mouths wider and their faces fold at the edges so they look like they’re crying, but they can’t. And Kayla sings louder. She waves her hand in the air as she sings, and I know it, know the movement, know it’s how Leonie rubbed my back, rubbed Kayla’s back, when we were frightened of the world. Kayla sings, and the multitude of ghosts lean forward, nodding. They smile with something like relief, something like remembrance, something like ease….Home, they say. Home. (pp. 284-285).

Although my Road Novel is nowhere near as dark (nor literary) as either of these books, it does share the theme of characters who are as dead set as the Bundrens on getting to their desired destination. Like both Faulkner’s and Ward’s stories, mine contains multiple narrators, characters who each have their own story arcs. Though they judge each other for their monomanias, they each have their own obsessions which blind them to the insanity of their quests. All this gives me a great sense of empathy for the characters in these novels who stand by helplessly as their Odysseus/Anse/Leonie plunges into their foolish journey which will lead to pain and family fracture. There is a reason we read these stories year after year, millennium after millennium. There is a reason why we keep writing them, too.

Bibliography:

Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying. New York, NY, Random House, 1930.

Homer. The Odyssey, translated by Emily Wilson. New York, NY, W.W. Norton, Inc, 2018.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Paris, Shakespeare and Company, 1922.

Miller, Madeline. Circe. New York, Hatchette Book Group, Little, Brown, 2018.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York, Random House, 1987.

Ward, Jesmyn. Sing, Unburied, Sing. New York, Scribner, 2017.

Additional Articles

Gans, Tristan. “Creation and Rebellion in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.” Inquiries Journal. (2011, VOL. 3 NO. 05). www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/532/creation-and-rebellion-in-william-faulkners-as-i-lay-dying

Green, Adrienne. “Jesmyn Ward’s Eerie, Powerful Unearthing of History.” The Atlantic.

Sept. 28, 2017. www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/09/jesmyn-wards-eerie-powerful-unearthing-of-history/541230/

Quinn, Annalisa. “’Sing’ Mourns The Dead, Both Buried And Unburied.” NPR, Sept. 6, 2017. www.npr.org/2017/09/06/547560046/sing-mourns-the-dead-both-buried-and-unburied.

[i] I used Emily Wilson’s translation for this essay. See bibliography.

[ii] Telemachi?

[iii] See Joyce’s Ulysses, p. 646. Interestingly, Ward also uses Molly Bloom’s “yes,” on page 284 in the end of that gorgeous passage I quoted at length in this essay.

[iv] See pp. 23-29, in the introduction to Emily Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey. She discusses at length the Greek concept of Xena—relations with foreigners.

[v] See Socrates Antigone and a kajillion other Greek texts.

[vi] See Genesis 22.

[vii] Sing, Unburied, Sing, pp. 250-256. To my mind, there is another hint of Abraham/Isaac in this mercy-killing, as River stabs the boy in the throat. Richie has run away from the penitentiary, and the wardens are going to find him and literally tear him to pieces.

[viii] “’Sing’ Mourns The Dead, Both Buried And Unburied,” NPR, Sept. 6, 2017, Annalisa Quinn.

The Comments

Join the Conversation. Post with kindness.

It would be interesting to throw Derek Walcott’s epic Omeros into this mix and see what it might bring! I’ve seen it referred to as a novel-in-verse, though I prefer to think of it as an epic book-length poem; either way you count it, Walcott manages to deftly balance both the road (or, often in his case, the sea) and the notion of being rooted to a place and to fuse the Classical with the Caribbean.

Oh! I have to read it, Michael. I’m working now on the essay about McCarthy and Groff’s novels. Also want to address Grapes of Wrath and Moby-Dick. Maybe you want to do a guest post on Omeros?