Countdown to Jam for the Fans Day 2

So I finished the song for the finale, except now it’s not for the finale. If we can arrange it in time, it will be somewhere else in the set….

Well, so my English 129 professor told me, anyway. Every tragedy traces its roots to The Iliad, whose “heroes” (principally Achilles and Agamemnon) place passion and hubris above reason. Their tragic flaws drive the plot in a straight linear fashion towards a fated conclusion. Similarly, every comedy contains traces of The Odyssey, a non-linear family road story that meanders through both time and place. Odysseus, the brilliant crafter, survives epic struggles to reclaim his position and his family. On the surface, at least, he wrests a kind of happily-ever-after with Penelope and Telemachus. Even his old dog Argus gets to nuzzle him one last time before he dies. Every writer since––consciously or not–– folds a bit of these seminal works into her own, as she contends with the legacy of her forebears while weaving something new into the telling. This is who we are, as writers—we are inventors and magpies. We are fabulously unique loners who get lonely and need someone to talk to.

Who do we want to talk to? Other writers, of course. We apprehend The Odyssey to understand our own journey, our own close call with that Cyclops who devoured so many of our fellows. We see our own complicated relationship with family; how we can yearn to return home and somehow fail to take the actions necessary to do so. We see how family members can act in unity but with very different motives. We see how our dead are never really silent; how we descend to the Underworld to commune with them, or how their legacy reaches into our lives until their ghosts become more real than the still-living mother who implores us to make better choices. We turn back to the writers who taught us and inspired us, and we say, “I love what you said about betrayal, but did you ever consider this?”

Although we all acknowledge that we “stand on the shoulder of giants,”1 we writers are an inquisitive and notoriously rebellious bunch. Novelists from James Joyce to Madeline Miller have taken the essential road trip yarn from the Greek and turned its moral on its head. They unravel the heroic threads of Odysseus’s personality and actions. They see more in his journey than the pure motive to do right by family. Each writer we fall in love with—each of our “giants,” if you will––provides us with choices in engaging in this perennial conversation with our forebears as well as our peers. In analyzing the story structure, imagery and technical elements of a given work, we see that writers are continuously drawing from both ancient and contemporary sources, both paying tribute and forging something original at the same time.

As many of you know, I have been working on a series of novels about The Big Idea, a folk-rock band composed of a core of siblings (Peter, Rhodie and Zhsanna Becket) and their rhythm section, Jack Spade and Mose Healey who, too, become family members of sorts over the course of the novels. I started these stories because I knew I had to write about my years on the road as part of another folk-rock band. What I experienced as an itinerant musician, traveling and performing with family members and lovers, gave me an education I couldn’t have paid for, an education that makes my time in an Ivy League institution pale in comparison. As Melville’s character Ishmael says of the whale ship he lived aboard for the span of Moby-Dick’s timeline, “It was my Yale College and my Harvard.” So was my Moby, the white fifteen-passenger Dodge Ram van we traveled within for the better part of the 1990s.

I spent decades trying to tell these stories, attempting to create a cohesive narrative out of so many experiences, but because of the way my mind works, the stories and characters just seemed to create more stories, more characters, with multiple voices and plot lines, until I had a sprawling, unreadable behemoth of a book. Most novelists, at this point, would have wisely given up and written about something else. Indeed, I took a long break from this work (2005-2012) during which I wrote two nonfiction books––How to Be and Adult and All Together Singing in the Kitchen––as well as numerous blog posts about raising my two children with my husband Tom all while continuing to be a touring and recording musician. But the stories of The Big Idea wouldn’t let me go, and in 2012, I slowly began working on them again. This meant reading novels, too, with an eye to try to figure out what a novel was, and how novelists achieved what I was trying to achieve. I also noticed all the different kinds of stories—bildungsroman from Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man to David Copperfield (and now, Demon Copperhead); novels composed of interlocking stories (Cloud Atlas, Cloud Cuckoo Land, Visit from a Goon Squad); and of course, the aforementioned road tales (Grapes of Wrath, The Remains of the Day, Sing, Unburied, Sing, As I Lay Dying). What kind of a book was I writing?

The problem for me was, to paraphrase Ira Glass, as a beginning novelist, my taste was just much better than my abilities. I read Colum McCann and Lauren Groff and despaired. Not only that, as a songwriter, my mind works episodically. The albums that we made over the years were simply records of what we were thinking, and I wasn’t always the only thinker. My first husband David wrote or co-wrote a number of the tunes. Katryna wrote, too, and so did Dave Chalfant. Even songs that were completely “mine,” were never solo projects; I always had the critical feedback of my producer and bandmates. The albums were connected, certainly, by texture and to some extent theme, but they didn’t necessarily tell a story with a beginning, middle and end. For novel-writing, I had to learn how to plot, to work with a timeline, to build a cohesive world. I had to learn how to develop a character, I had to learn how to show interiority without telling too much. I had to learn narrative pacing, what to leave out as much as what to include.

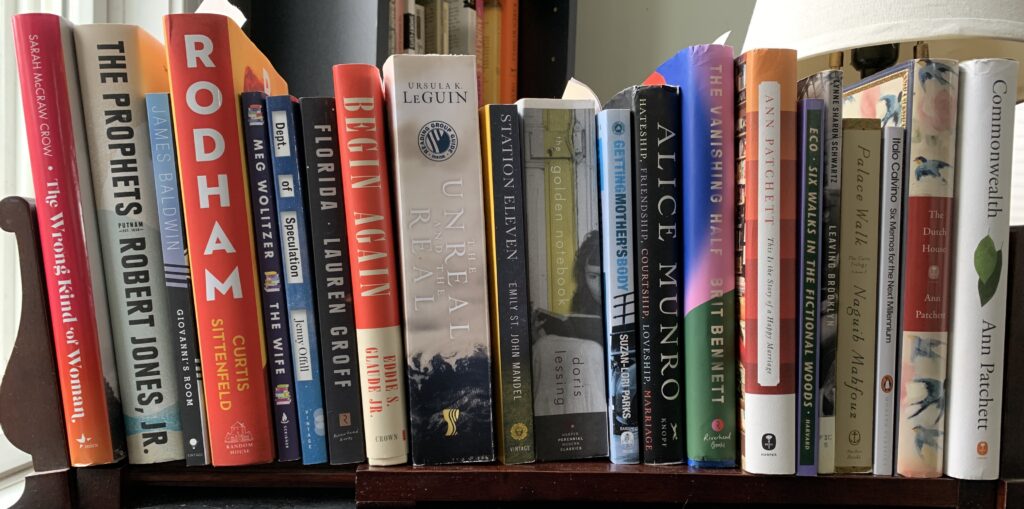

Eventually, the pandemic gave me permission to return to a more formal education, and I earned my MFA in Fiction at Vermont College of Fine Arts. Here, I read literally hundreds of books, scores of articles. I became obsessed with novels, reading voraciously to the tune of approximately 50 books a year (a practice I continue to this day, over a year post-grad).

At the time of my graduation, I concluded that the many stories of The Big Idea were too numerous to be contained in one novel. The world of my characters had become too real to me, the characters have entire lives now, they couldn’t be squeezed and compacted in the ways I had tried to mold them. Neither could I write nothing but road tales. A series of books began to appear on the horizon. I made the decision that I would write these books one at a time, starting in the beginning with a bildungsroman (coming of age) structure. I am the verge of completing this first book, Pimmit Run, and while the draft is being pored over by my editor, I wanted to begin publishing some bookish essays about what I have discovered, starting with the category of books we’ll call adventures2––these Odyssey-based road tales: what I learned from them and what I might apply to the second book in my series, the one about the years the band was on the road. Next week, I’ll post a discussion of the continuities between William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing. I hope to write another on Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Lauren Groff’s The Vaster Wilds. But my editor might just return my manuscript and then I’m back in the cave for a few months. In any event, please let me know in the comments if this topic–book discussions–is interesting to you or a total snooze-fest. Rest assured to the latter reader: I’ll soon return to discussions of hair ties, performances, politics and whatever other nonsense I feel obliged to write about.

Join the Conversation. Post with kindness.

Love the writing/book discussion! Please continue

Thanks, Celia! That means a lot coming from a reader like you.

On board your ship, Captain. Sail on!

Yay! Thanks, Anne!

As a dear former colleague of mine would say, Bring it, sister! 🙂

Thanks, Elaine!

More essays please. Lots to learn, lots to discuss.

Thanks, Jeff!

Absolutely interesting! As a good friend once pointed out to me, the only original idea in the Universe is when one cell decided to split and become two. We’re all magpies and borrowers 🙂 Or, stealers if you ask Picasso (“When I can steal, I steal.”) Keep it coming! (Jamie Potter, Potomac ‘96 – ‘99)

So uncanny, Jamie–right before I read your comment, Tom was reading out loud the back jacket quote from the novel he just got to read, Of Kids and Parents by Emil Hakl. Here’s what it said:

“Nothing’s been new in this world for more than two billion years, it’s all just variations on the same theme of carbon, hydrogen, helium, and nitrogen.”

Yes, more of this please

Yes, please, Nerissa! Always interested in the workings of a brilliant (and constantly learning) mind! You go, girl!!

Thank you, Linda! That means a lot coming from YOUR brilliant and constantly learning mind.

Moby!

I recently retrieved the orangey-yellow 1972 VW Camper that I bought in 1994. It could be found in many of the same northeastern parking lots and festival venues as Moby in the mid-late 90s as my 20something self gobbled up as much live music as I could. I took the aging van off the road at the end of the decade and stored it in an outbuilding of my friend Bill’s farm in New Jersey.

Bill was a generation older than me, a Vietnam vet who was a brilliant mechanic and archivist of machines and the history surrounding him. He passed away after a prolonged battle with the compounded ailments that plagued so many of his fellow veterans. Friends and his widow worked to get the stored cars and such off the property and consolidated most of his collection in a metal barn where they comprise a semi-secret museum, with placards made by Bill over the years describing each car, truck, bike, or implement.

We gathered earlier this year in the barn to eat, drink, and remember Bill’s stories and his dedication to the stories of historic machines and the long-gone people who designed, made, and used them. My partner and I were among the youngest in attendance, in our late 40s. It was a gift to hear so many stories and a little poignant to know that many of them won’t outlast their 70/80/90-something tellers. We visited another Jersey friend, a close friend of my late mother, whose amazing life could fill volumes and movie theaters if anyone could adequately capture it.

I’m grateful for all of these stories, and the work that you and others do to return to them and share them when they persist in memory and remind us they need telling.

Oh, what a wonderful story, Christopher! Go 1972 VW van!