Gospel of John, Lennon: Darkness and Light

posted December 9, 2014

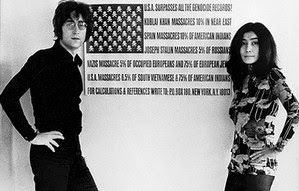

Can it really be thirty-five years ago that John Lennon was murdered? He was 40 at his death; soon he will be 40 years gone. I keep checking my math, and it’s undeniable. I was in eighth grade in 1980, finally shedding some of my insecurity, and just beginning to express myself as a singer and songwriter. John’s death had a dramatic effect on me; I responded by immersing myself in his biography, learning everything I could about him and Yoko. Something in his outlaw identity matched my own adolescent mood, perhaps. At any rate, in reading about him and his courage in the late 60s when he took an idiosyncratic stand for peace (think bed-ins, think “Christ, you know it ain’t easy”), it occurred to me that I didn’t need to spend all my energy, as I had been, worrying about what everyone thought of me. I began the slow process of understanding that I was an artist, and therefore had a mission for the world. I wore black to school (instead of the requisite blue uniform), spoke out for peace, and came home to close myself in my bedroom with my Beatles and Lennon LPs. After months of this, I emerged a different person: braver, more ridiculous, perhaps, but definitely braver.

Of course, Lennon’s death meant something to millions of people. And certainly thousands if not millions of 13 year olds. I could have told this story very differently. I could have said that during this same time my grandfather was dying of cancer, and that my deep grief for the former Beatle was simply a mask for my sadness over losing my grandfather. I could have interpreted my reaction as plain old adolescent drama, but the fact that I claimed it as a positive personal myth shaped the way I have grown into a person. I am glad I saw things the way I saw them.

My Underground Seminary has been reading Richard Rohr’s meditations for Advent this December, and today’s reading was on darkness and light. The Gospel of John says “The light shines on inside the darkness, and the darkness will not overcome it.” (1:5). Rohr goes on to say that “We must all hope, and work to eliminate darkness…but at a certain point, we have to surrender to the fact that the darkness has always been here, and the only real question is how to receive the light and spread the light…What we need to do is recognize what is, in fact, darkness, and then learn how to live in creative and courageous relationship to it. In other words, don’t name darkness light. Don’t name darkness good.”

This is a challenge to me and my theology. I want there to be a silver lining in all darkness, and I want to go farther than that. I want the silver lining to actually redeem the darkness, make the darkness worth it. But how dare I say that Lennon’s death was worth it because I got inspired? Or that the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner might lead to a national re-thinking of racial profiling? The people who love them might want that too, but I bet they want their son or brother or friend back more. I wanted to think that something would change after Columbine, after Sandy Hook. But nothing changed that I could see (though my optimistic self wants to cry, “But the story isn’t over yet!”).

How do we tell the story? A baby was born in a manger, born into the generosity of the barnyard animals; born in the cold shrug of the innkeeper who wouldn’t give a room to a pregnant woman in labor. A prophet healed the sick and cured the lame and made the blind to see, and preached liberation theology and encouraged the believers to question the authorities and pluck grains on the Sabbath, and was executed by the Roman government in a hideous, slow, public way. And then his words got twisted for millennia and millions were murdered in his name. And along the way, many people derived great consolation from his teachings and the example of his life. Many found enlightenment through following him.

My son has had a difficult fall, in some ways. For the first three months of school, he dragged his feet every morning, clinging to his Legos, our legs, refusing to get dressed some days, even weeping as he trudged up the stairs and through the school doors every morning. We held him, we comforted him, we gave him consequences. We talked it over with his teacher, a wonderful women whom our older daughter had had, and whom we loved. Maybe she was the wrong fit for our son. We considered asking the school to switch him to a different class room. I fantasized about home schooling him (for about three seconds.) Finally, I consulted my parenting Bible, How to Talk so Kids Will Listen and Listen so Kids Will Talk by Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish. The next time he threw himself on the carpet during morning violin practice and yelled, “School is stupid! I hate school! Teachers are stupid!” I took a page from the book, and instead of trying to reason with him, as I usually did, (“Well, you might not like school, but it actually is the opposite of stupid,” and “it’s not very nice to use that word about anyone!”), I gave him a piece of paper and said, “I am so interested in how you are feeling! Could you show me so I could understand? Why don’t you draw a picture of that!” So he did. He drew a stick figure of himself, and then a bigger stick figure of his teacher. Then he drew a line from his hand to her head. He paused and said, “How do you spell ‘lightning?'” I paused too. Anger was one thing. Homicide another. But as I looked at my boy, I thought, he needs to know his anger is okay, and this is exactly the way I want him to express himself. So I gave him the correct spelling, and when he took his marker and scribbled out the teacher’s face with it (because, of course, the lightning had blown her head up!), I said, “Wow, you are so mad at her!” and nodded. He looked up at me, a satisfied look coming into his little face. This was right before Thanksgiving vacation. I didn’t hear any more complaints after that, and in fact noticed that he was a lot lighter and easier going. Last Friday as I was kneeling in front of him to zip up his winter coat, he said, “I love school, mama. I don’t hate it any more. I can’t wait to go to school!”

“Really,” I said mildly. “What changed?”

He shrugged. “I just grew into it.”

Yet as I write this, I know that, for myriad reasons, some mothers don’t have the freedom to trust their son’s (or daughter’s) darkness. I don’t claim to have the solutions to how we eradicate racism or violence. I just know that the frame that the story comes in is extremely important. And I would add to Rohr’s admonition to call the darkness darkness and light light, that some of that discernment is in the eye of the beholder. And that, as we all have darkness, we need to stop being so afraid of it. I think it helped my son immensely to have me come into his darkness and witness it and not tell him that he needed to be afraid. Maybe by saying, “Wow, you are really mad!” I was simply naming the darkness, and affirming that “mad” was an overlay. “You” are full of light, and this is just a dark spot on your essentially light background.

I have been lucky enough to outlive my own fears of the dark––of my own dark, anyway. Over the weekend, Katryna and I played a show in Virginia and got to hang out with my parents who are two of my favorite people who ever lived. Long gone are my adolescent conflicts, my petty criticisms of what I once called their bourgeois lifestyle. All that’s left is sweet, gentle, tender love, and more gratitude for them and to them than I can ever communicate. When I went through my own series of crises in my late twenties and early thirties, I was taught how to shine a light in my own darkness and untangle the stories, see them as just stories, frame them appropriately and make my amends; move on. Once I did that, forgiveness ceased being a choice; it became as obvious and necessary as breathing. Forgiveness seems to me a river at the base of it all, underground, like the river Styx, perhaps, and that when I get baptized in that river, I come out clean, and able to endure the beams of love, which were there all along. We all shine on, as John Lennon said. Shine, baby, shine.

Thoughtful, compelling, and honest. I remember hearing about John’s death from Charles Laquidara (WBCN Boston) and feeling disbelief then numbness. I always found inspiration and perspective in lyrics, a model in his actions. His death seemed so random and senseless. Thirty-five years hasn’t changed that. I often wonder what John’s voice could contribute now. He was a complex man with many failings, a human being who grew and learned to give to the world. Thanks.

I was under the ocean on a nuclear submarine when I heard the news. It was so hard being isolated from the world, not having the chance to grieve with everyone else.

There has always been a hollow place in my heart for John ever since.