Changing My Mind

…But her soul, only partially unpackaged, singsthrough the slate that guards it, contacts those of us waiting here with a splay of its softscrutinizing fingers. Her soul is a sapling…

Greta Gerwig’s Little Women (2019) is a master lesson on the art of revision and narrative structure. As I watched it for the second (or maybe third) time, I thought about what I could learn from Gerwig in terms of my own struggles with revision.

Every writer has to contemplate the problem of structure. What goes where? Novels often begin from a present-day perch; here, the narrator knows from the very beginning how the story will end––and we know that the narrator knows. Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield begins his tale at his own birth, but it is the grown David looking back who tells it. On the other hand, Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre begins with young Jane, an orphan stuck living with her cruel aunt. The narrator has no idea yet what will happen to her, bringing the reader on a very present-tense journey. The question of where to begin and how to reveal what we want the reader to know while deliberately holding back the juicy surprises never gets old.

Gerwig re-structures Alcott’s beloved novel by beginning towards the end of the original story, with the heroine Jo March as a young adult getting her first story accepted for publication. The viewer, meeting Jo at this point, knows immediately that she is an ambitious, hard-working writer, and that she’s up against a tough business, personified by Dr. Dashwood, editor of the Weekly Volcano who is interested only in lurid stories and heroines who end up properly married, “or dead.” It is only after seeing her New York City world––including the attractive French musician who clearly has the hots for her–– that we move into the past, to the scene years earlier when the four March girls are anticipating a present-less Christmas, where Alcott begins her novel, where Jo is still a girl with literary dreams.

Gerwig uses clever visual techniques to guide the viewer between the two timelines, bathing the past in golden light (childhood, which Jo romanticizes and grieves the loss of) while the present is shot in clear blues. [NND1] If this were a written revision, we might need some other technique to guide us between past and present, and made me think of other visual ways I could distinguish my own interweaving timelines on the page. I could use present tense for present day and past tense for the past. I could use different fonts, as Anthony Doerr does in his most recent novel Cloud Cuckoo Land. Or I could simply add the date at the top of each chapter or scene.

The film version of Little Women is substantially shorter than the 800-page novel, but I was impressed with Gerwig’s other methods of economy. For example, she draws the relationship between Marmee and Papa Alcott mostly through subtext. We are told very little about their relationship, but we know from slight sketches what that relationship is like: Marmee’s own struggles with the rage Jo feels; a few choice remarks Laura Dern tosses out at the dinner table in her husband’s presence; even tarter remarks by Meryl Streep’s Aunt March. All these clues point to the trials of being married to a man whose idealism drives his family’s comfort.

Readers, as Lauren Groff says, understand that there are rooms they don’t get to enter in a fictional world.

Most of all, Gerwig reframes the entire story from a cozy collection of memories and anecdotes to a love story. Gerwig’s choice to begin where she does cements our conception of Jo as an independent woman who seems to be taken with the handsome Frederick who, in Gerwig’s version, is not the poor, middle-aged German papa stand in of Alcott’s book but a very handsome French musician who can dance a mean contradance. His critique of Jo’s writing, which we see soon after we meet him (but also after we notice her attraction to him) comes across not as the mansplaining Alcott’s Frederick’s does, but rather as evidence that he truly sees Jo’s potential and talent. I, like many a young girl reading Little Women, could not understand why Alcott married our wonderful Jo off to that boring old guy when deliciously funny, adorable Laurie who was practically a family member offered his hand. If Jo’s greatest pain is the loss of Meg, her older sister, and all that Meg represents (“I can’t believe childhood is over”), then why wouldn’t she flee into the arms of the next best thing, her neighbor/brother?

Alcott herself never married, and many assume she preferred women. That’s a reasonable and satisfying assumption, but it doesn’t help the fiction writer in figuring out what her characters want. Gerwig’s Meg sees something in Jo that Jo herself can’t yet see––not, as Meg thinks, that Jo will one day fall in love with a man, but rather Jo will find something she loves more even than her family. And that is writing.

For this, it turns out, is the true love story, the one between Jo and every aspect of the art and craft and labor of writing. In fact the movie itself seems in love with that particular art form. To wit: the grief and fury we all felt watching Amy burn Jo’s manuscript; the beauty of Jo’s pages laid out on the boards of the floor to be marked up, edited, moved around in the same way the filmmaker has moved scenes. The ending with the labor intensive process of fabricating just one physical book. Each letter set just so.

Much has been made of Gerwig’s clever ending, where Jo races to the train station in the rain to stop Frederick from leaving for California and declares her love. The storyline pauses to shift back to the potential editor for the story, who insists that Jo marry. She can marry Laurie or Frederick, it doesn’t matter, but if the writer wants to sell books (which she does, unlike her poor father who drove his family further and further into poverty by stubbornly publishing work that antagonized the general public), then she must sacrifice her character to a heterosexist, orthodox union.

Nevertheless, the writer wins. She gets to hold that book in her hand, and that, after all, is the point of the movie. The story question is: how can this poor young woman make a living writing? Jo wants to be a writer. She gets, in the end, what she wants. The dude is gravy.

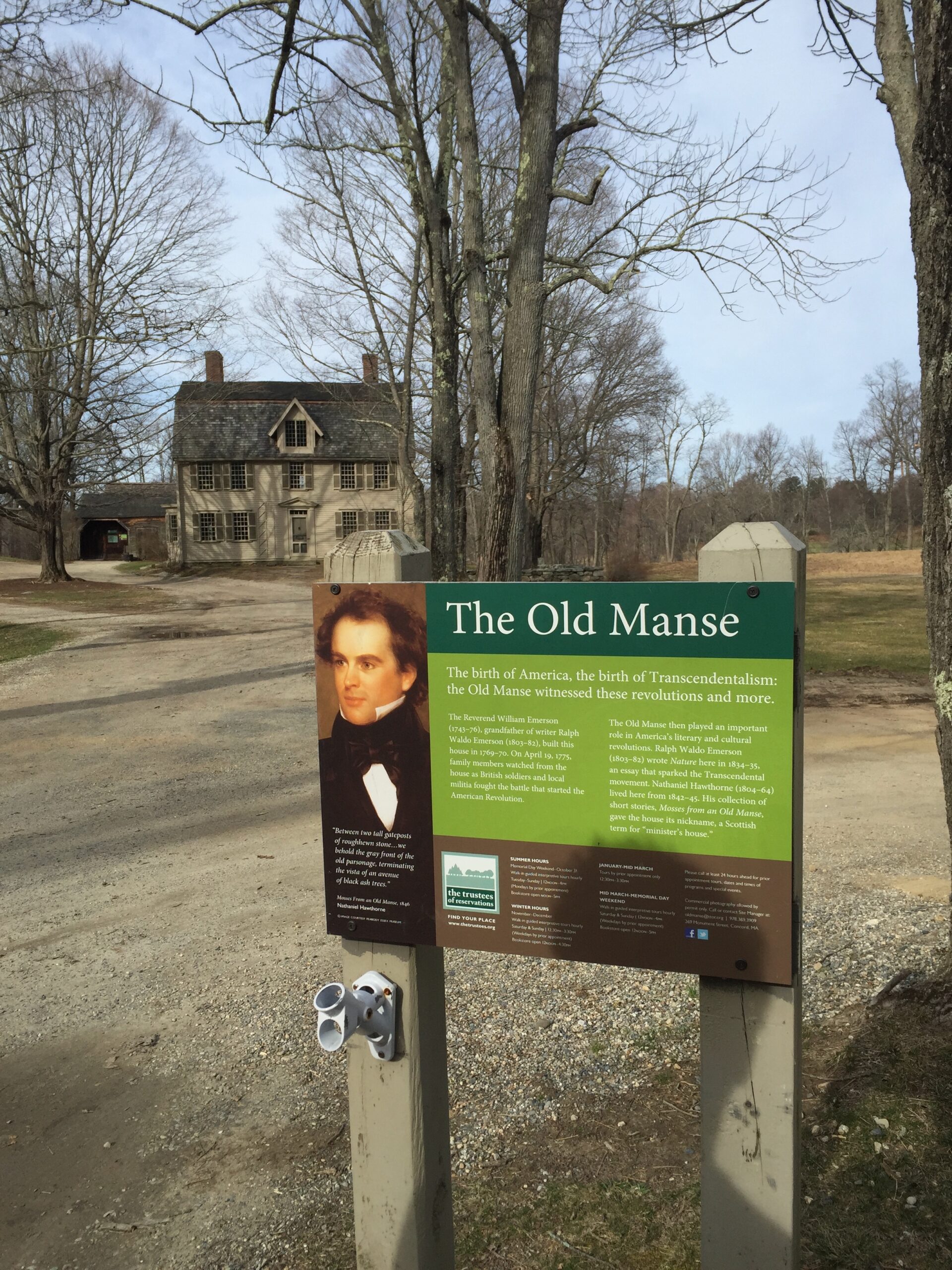

PS. Gerwig shot the entire film in various Massachusetts locations, which made my proud little Massachusetts heart sing—part of the reason I chose to live here I’m sure is my lifelong obsession with all things Concord: the transcendentalists, the abolitionists, the writers Hawthorne, Thoreau, Emerson. And, of course, both Alcotts.